Beyond Disavowal

What To Do When We Can't Just "This Is Fine" Our Way Through This Mess

I live in a part of the country that is currently1 dealing with significant air quality issues due to wildfire smoke that is being carried through the atmosphere and transformed into even more toxic particulates. This now happens multiple times a summer and each time, the impacts on my well-being are noticeable and swift. My plans for early morning bike rides in perfectly cool summer mornings were thwarted this week, which knocked off my whole routine and robbed me of one of my more enjoyable and easily-motivated-towards forms of physical movement. I have spent as little time outdoors as possible, reducing my exposure to sunlight and fresh air, and meaning I’m spending way less time in my mindful practices of bee watching and listening to birdsong.

And I am forced to confront climate change. There’s no effective way to pretend it’s not happening when our skies are visibly hazy and I’m donning an N95 to spend any time outside. Even inside my house as I’m sitting with clients or writing this, the windows in my view showcase the toxic haze.

Stripped of the biological, psychological, and social benefits of my outdoor summer movement while not being able to turn away from grim truths about the state of our world and the future of our environment and our lives on this planet… rough combination, friends. And I’m feeling it.

What do we do when we can’t look away from incredibly difficult realities?

In many ways, this is the question oppressed people have been asking and answering forever. And it’s the question a lot of less oppressed people in the U.S. have been asking since Israel started its most recent leveling of Gaza and since Trump took office and amplified existing governmental violence and enacted new forms, as well. Many of us who have had the privilege to not be directly impacted grew up coping with the knowledge that there is suffering, that the environment as we know it is collapsing, that the governmental and social rule we are complicit in does harm… by looking away or holding that knowledge at a distance.

And some people continue to use this approach. But for many or even most of the folks who had effectively used disavowal as our primary defense against shitty realities, the haze has settled into our view and lungs and we can no longer pretend (for very long anyway) that these things aren’t happening/ true.

I am going to use this substack post to dig into alternatives to disavowal when we can’t or no longer want to look away. I’ve included a lot of images and video, so it doesn’t all fit into an email. Make sure you click through at the end of the email to read the whole thing. And consider supporting me by upgrading to a paid subscription so I can continue to dedicate time to writing longer form pieces like this.

First, a little about disavowal

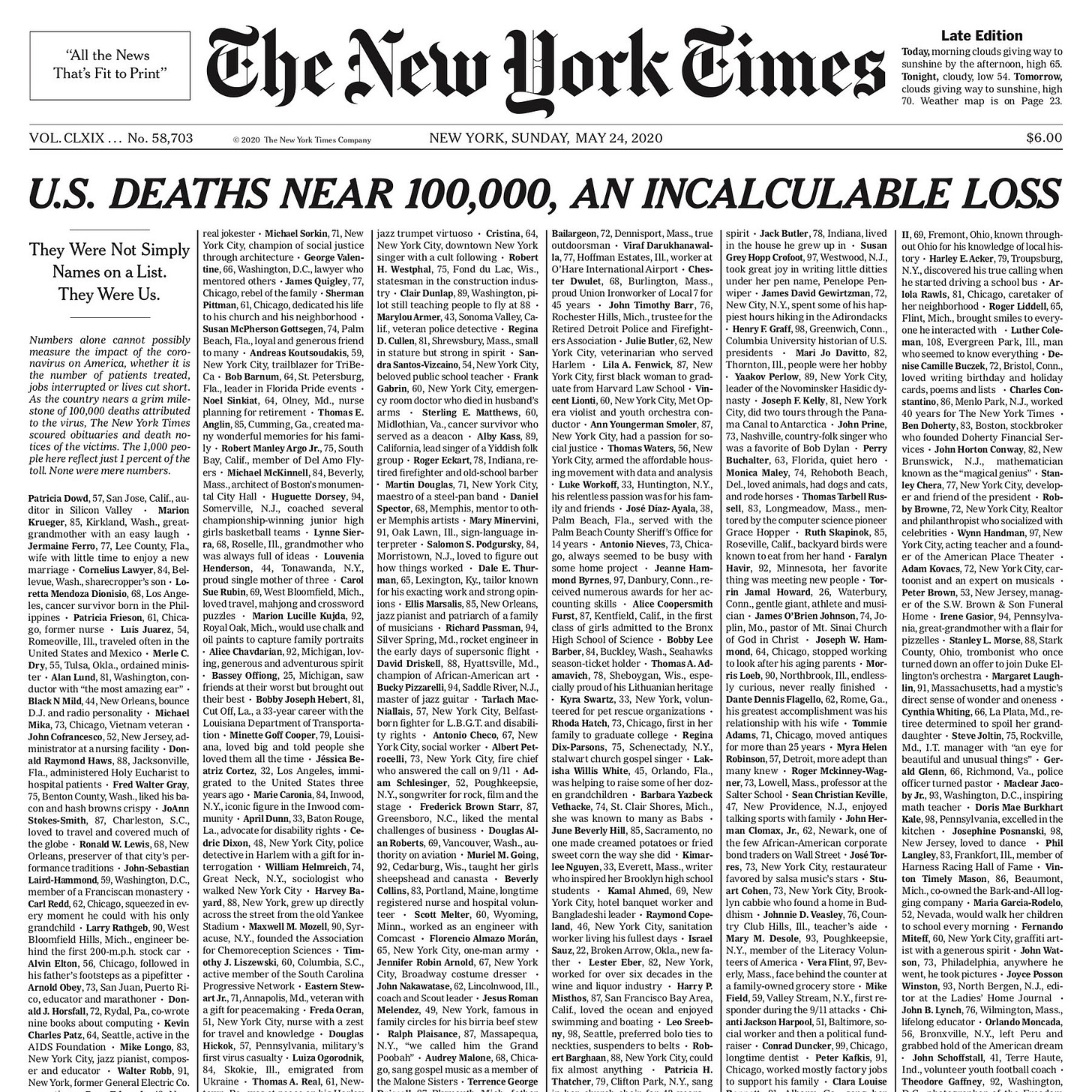

Disavowal is one of the concepts I learned in my psychodynamic training that has its roots in psychoanalytic theory and is incredibly useful. (If you hang out with me for long enough, you’ll learn that I think much of psychoanalytic theory has gotten a bad rap and is actually quite useful.) Disavowal is one of our core defenses against truths that are too difficult to experience as true, at least for very long. This is the experience of knowing something is happening or true but holding that knowledge at a distance. Knowing and not knowing. It’s not denial or repression, where our very awareness of the truth is defended against. It’s more of a split. I know this is happening but I must act as though it is not and hold that knowledge outside of my moment-to-moment awareness. The “this is fine” meme could be understood as potentially representing disavowal.

Either it’s disavowal or this dog’s powers of denial are strong. But if we assume that this dog is aware of the fire around them and finding a way to go about having their coffee as they would if fire were not all around them, that’s disavowal.

When a psychoanalytic mentor introduced my peers and I to the concept, he described it as the primary way we defend against our own mortality. We know we’re going to die one day, but we have to hold that knowledge at a distance and not experience knowing it, or else most of us would collapse under the constant fear and despair of our own certain death.

I’m not quick to criticize people for their disavowal of the horrors of this world. We largely do this because we have a limited a capacity to metabolize trauma at such an immense scale and we do it because we’re told (and it may be true) that the things right in front of us - getting the kids to school, fixing the plumbing, helping a neighbor, succeeding at work - are really important to get done. Sometimes disavowal even helps us be better activists or community organizers. It may be hard to draw energy toward resistance and forward movement and community connection when we are weighted down by the suffering (and perhaps our guilt at not experiencing the direct suffering and threats that others do, when that is the case).

And also acting as if “this is fine” when things aren’t fine, especially when we’re not being as directly impacted and have more capacity to do something about it but use disavowal to help us feel better about not taking action… Well, that’s harmful. If you’re outside the house on fire and you know the dog is in there, saying “this is fine” so you can go about enjoying your coffee means the dog — whose lungs are filling up with smoke and is way less equipped to get themself out of there or fight the fire — doesn’t have your help in putting out the flames.

And if you’re the dog in this scenario, as many of us increasingly are, “this is fine” keeps you in a burning house.

If not “this is fine,” then what?

Surviving the dissonance and confrontation disavowal protects us from

The first thing we’re tasked with when we move away from disavowal is bearing the experience of really taking in the knowledge we’ve been trying to keep at arm’s length. If that was easy or painless, we’d not have needed to turn away or disavow in the first place. Again putting on my psychoanalytic psychologist hat for a minute: I want to talk about psychic coherence. Psychic or psychological coherence is the internal experience of alignment between our thoughts, beliefs, feelings, and behaviors - and our ability to make consistent meaning of these pieces and how they relate.

Often we use disavowal to push away a piece of information or emotional experience that if fully internalized would contradict with parts of the rest of our internal experience. In other words, holding it in mind as truth would challenge how we make sense of ourselves or others or the world.

If we take climate change as an example, it’s easy to see how quickly destabilizing to our coherence ecological disaster can be: It feels good to be outside and I believe it is generally safe and even health-promoting to be outside and I am making plans for my future that assume this doesn’t shift. My psychic coherence is built around this sense of stable safety and well-being outdoors. The wildfire smoke and consequent toxins in the air remind me of truths that are contradictory to my existing way of viewing the outdoors. Disavowal of the wildfires, of air quality alerts, etc. (when they’re not happening in my area) helps me preserve my coherence.

If you believe humans are generally good or that our government is a generally benevolent force in the world, knowledge of U.S.-caused or -complicit human suffering disrupts your psychic coherence.

If we believe that we are people who act in accordance with our values of justice and protecting the vulnerable, then recognizing the extent to which immigrants are inhumanely treated (literally to the point of death or lifelong traumatic impacts) in our country’s tax-payer-funded detention centers while we go about our day jobs and casual entertainment, etc., will disrupt our sense of psychic coherence.

Cognitive dissonance describes the psychological experience we have when we try to believe two majorly contradicting things. Dissonance is both intellectual and felt for me. It’s like a fuzzy shaking my brain does. Without disavowal, the first thing we experience is dissonance. Our minds go “aaahhh these things aren’t consistent, something is off, something is wrong! aahhh what … even … is … this?!?” At least that’s what it’s like in my mind. “I’m a person who would sacrifice my comfort to help a person who is suffering. I am also sitting at home in my air conditioning eating pizza while somewhere in this country (probably a drive away) people are being detained in overcrowded facilities, treated abusively, and denied medical care” aaahhh these things aren’t consistent, something is off, something is wrong! aahhh what … even … is … this?!? At this point, often times, disavowal returns. Sometimes an even stronger defense like denial steps in. We distort the facts and our feelings and beliefs about a situation to not disturb our coherence: “well only the immigrants who have done terrible things are put in those centers” we might tell ourselves (though to be clear, this is not true), or “the conditions aren’t that bad” (again, decidedly not true). “Fake news!”

Without using those defenses, our other option is to confront the inaccuracies in other parts of our internal belief system. “Ah, maybe I’m not as principled as I thought.” “Maybe I don’t always act in accordance with my values.” “Maybe my values aren’t really what I thought they were.” “Maybe the safety of the outdoors isn’t something stable I can count on.” “Maybe America was never good.”

The opposite of disavowal is reckoning.

If not, “this is fine,” then “this is not fine.” In some ways it’s as simple as that. That’s the answer. We acknowledge this world is not fine and this is the world we’re living in.

We have to feel and tolerate the moral injury, complicity, disillusionment, guilt, shame, fear, grief, and hopelessness - even loss (or evolution) of identity, that come with disrupting how we view ourselves and others and the world.2

And then, we can figure out what the heck we want to do.

Meaningful living alongside difficult truths

If the world is not fine, how do we live in it? Let’s go back to our dog friend. An anthropomorphic dog in a burning house has a number of options:

Escape the fire and/or call for help

Fight the fire, protect themself from the fire, and/or delay or minimize pain from burns and structural damage

Live meaningfully in the time they have left, knowing the fire is coming for them — maybe call a loved one so they’re not alone?

What are the equivalent responses for us?

GTFO or at least resource ourselves and engage in harm reduction

I don’t know how much we can escape the fire at this point, my friends.3 There isn’t a place on this planet that is not affected and will not increasingly be affected by climate change crises. There is no ideally functioning country that offers effective governance and civil liberties for all, and if there were, we wouldn’t all fit. There is no experience on this planet right now where you are free from sharing humanity and the world with people who are being systematically starved to death. I think this is why the original meme resonates. If we’re trapped in a world on fire without escape, the pull to just disavow or even deny the horror is pretty strong.

But we can resource ourselves and others. We can slow down the destructive changes. We can mitigate the harm on us and on others.

I am reminded of a piece of an exhibit at Mass MoCA: Belly of a Glacier by Ohan Breiding. Breiding documents how residents of the small village of Obergoms, Switzerland, drape the remains of the ever-melting Rhône Glacier in a geothermal textile to protect it as best they can from the warming each spring. As best they can.

Take meaningful action consistent with our actual capacity - be creative

Action helps restore a sense of agency and a sense of living in line with your values. Consider options for community-based action; think realistically about your spheres of influence. You may not have a huge platform or be charged with enacting policy that affects a large region or group of people. You can still lobby those who do have those platforms or roles. You can also affect change using the influence you do have — at the community level. Are there land trusts and conservation efforts in your area? I bet they need volunteers. Hell, just planting milkweed and native pollinator gardens can make a significant impact on the ecosystem around you. Another example: Do you live near a weapons manufacturer? Can you disrupt their shipments and make it hard for them to do business? Another example: Maybe you aren’t particularly well-positioned to prevent hospitals in a different state from shutting down care for trans people under age 19, but if you live near somewhere that still offers care, you could connect with them and/or your local PFLAG and offer families traveling for care a place to stay. If you live in an area where care is inaccessible, you could offer to donate travel points to young people and families traveling (perhaps through a larger org like the Campaign For Southern Equality’s Trans Youth Emergency Project). [By the way, if you want more ideas for supporting trans people, there’s a whole ass guide for you written by Anna Marie, PhD: https://www.thatannamarie.com/help.] Another example: If you’re a man concerned about the male loneliness epidemic and toxic masculinity, how are you modeling and reinforcing non-harmful masculinity in your interactions with others? Can you facilitate friendship and social opportunities for men in your neighborhood? Another example: divest personally from companies that profit from harm - consider participating in the BDS movement and make sure your investments aren’t supporting private prisons. Encourage others to do so and campaign for the institutions you are connected to do divest.

In considering action pathways, we also have to honor our limitations. The capacity (whether it is time, energy, aptitude, etc.) for any given action is going to differ between people. Even for one person, your capacity will be dynamic across time. And limitations that might require small(er) actions aren’t an excuse to do nothing. Something is always better than nothing, from both a psychological well-being standpoint and in terms of impact.

Something else I must mention in this section: give yourself permission to not take action on every issue. I wrote earlier that disavowal is partially about the sheer scale of trauma that we are trying to bear witness and respond to. We have to trust that taking meaningful action in some areas will have impacts that reach beyond those specific spheres.

Relevant to both the issues of sphere(s) of influence and capacity, work with other people! Again I am reminded of the villagers of Obergoms, working together to preserve the glacier that is critical to their ecosystem and ways of life. Ideally, join efforts spearheaded by members of affected communities. For example, the most effective initiatives to meaningfully support undocumented immigrants and center their needs are likely going to be the ones led by immigrants who are undocumented, have been, or are intimately connected to people who are — see Carolina Migrant Network for an excellent example of this.

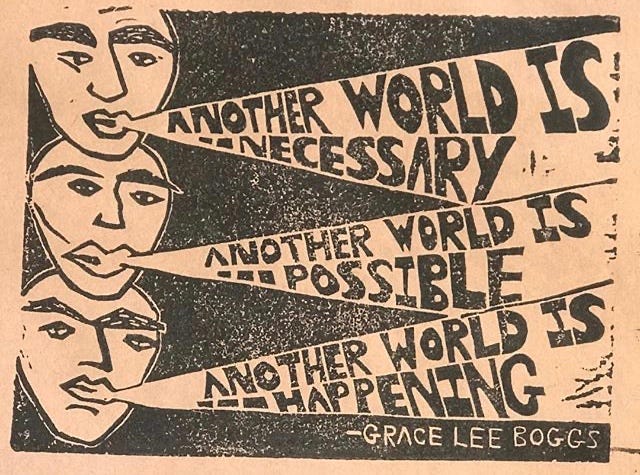

Keep your imagination of better futures alive

In her new-ish song A World of Love and Care, Ezra Furman sings, “Do you ever imagine a world of love and care? What would you be doing right now if you lived there?” Part of how we develop creative ideas for how to take action is by keeping our minds open to possibility. Evict the fascist in your brain that wants you to give into subjugation and nihilism! Dream of a better world and imagine what you would be doing in that world - then do that thing, or something that moves us toward the possibility of doing that thing. If we have any hope of humanity surviving the present and future climate crises — and of disrupting the environmental racism and classism that puts racially minoritized communities and lower-resourced communities more directly in harm’s way — then we will need to think outside of our current ways of understanding our relationships to the environment. Abolitionist Mariam Kaba has spoken and written often about the importance of using imagination to resist internalizing a false belief that the way things are or have been (specifically in her work - policing) is the way things have to always be. She wrote, “if something can’t be fixed, what we do we build instead? …Imagination is required because we need to invent new worlds and new ways of being with each other. We have to pre-figure the world in which we want to live.”

Find purpose and joy and stay connected to others

In case you’re losing the metaphor that I’m insisting on clinging to (in part because I spent so much time making those graphics), this point is the analog to the dog calling their cat friend while the house burns. I know good coffee is really wonderful, but something tells me that if that dog was really accepting that their house was burning down and they were stuck there, they wouldn’t want their last moments to be spent drinking a cup of coffee alone. When we arrive at “this isn’t fine” and “this is the reality of the world I am in,” a question worth striving to answer is then “how do I want to live in this world?” This is the “don’t forget to sing in the lifeboats” bit - the “joy, still” bit.

Confronting difficult realities doesn’t mean we never get to experience joy or meaningful connection again. Quite the opposite: joy and connection become vital in such circumstances. Solidarity, community, love, care. Seek these out and invite them in.

We must also grieve (together)

Another piece of the Breiding Mass MoCA installation I referenced above was a staged funeral for the Rhône Glacier. In the written guide to the exhibit, the Mass MoCA curators noted that in 2019, Iceland held the first funeral for a glacier lost to climate change. Since then, multiple similar funerals have been held and artists and activists are working to create rituals and sites of collective grieving for and memorializing of our mounting environmental losses. There’s much we can learn from the Climate Psychology Alliance and the Climate Psychiatry Alliance and their work on coping with climate-related distress. On their resource page they offer two poignant quotations:

“This is a dark time, filled with suffering and uncertainty. Like living cells in a larger body, it is natural that we feel the trauma of our world. So do not be afraid of the anguish you feel, or the anger or fear, because these responses arise from the depth of your caring and the truth of your interconnectedness with all beings.” ~ Johanna Macy, Buddhist scholar, environmental activist, workshop leader, in The work that Reconnects.

“When we push away our feelings, we risk …..losing our connection with our caring selves. “ Grief can make us come alive and point us towards life’s bigger purpose amidst climate breakdown”. ~ Brittany Wray, climate scientist, researcher, and author, in Generation Dread

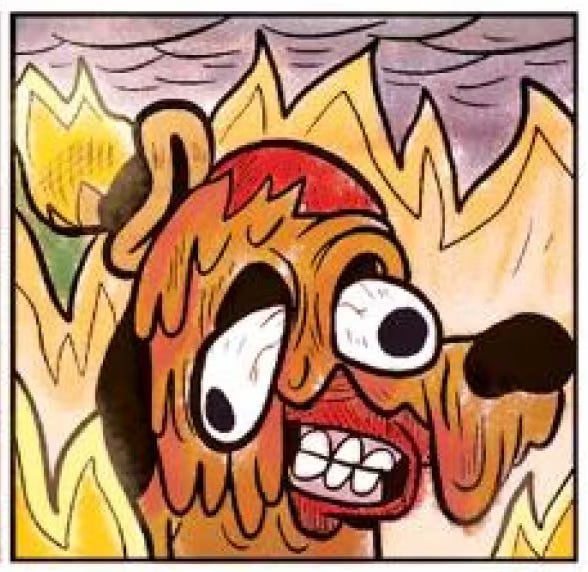

I have also been grateful for the opportunities for collective grieving for the lives lost in Gaza that many of us are witnessing through our screens — the art installations and the therapist- and death-doula-led grief circles. I am reminded of the efforts4 to grieve and memorialize the lives lost to COVID-19 (both in terms of actual deaths and the losses of aliveness and “normalcy” and connection so many of us experienced and/or continue to experience).

“Do not be afraid of the anguish you feel, or the anger or fear, because these responses arise from the depth of your caring and the truth of your interconnectedness with all beings.” Honor your feelings and be grateful for them. They stem from and represent your humanity and interconnectedness to others. And our feelings also honor the lives lost or suffering, and honor our own suffering. Seek out ways to mourn and rage. Create opportunities for experiencing these feelings. And it doesn’t necessarily need to be formal or organized specifically around grief. Some of my most powerful emotional catharses have been in the audiences of concerts and dance performances. (Like when I wept while watching ANOHNI perform Another World at Mass MoCA in front of footage of Marsha P. Johnson and dying coral reefs.) Or on solo bike rides. Though I do think experiencing and expressing these feelings in relationship with others or collectively in groups can be particularly valuable.

And hey — don’t let go of disavowal completely

I want to close with a clarification that this is not a call to give up the precious defense of disavowal entirely. We are doing no one, including ourselves, any favors if we are flooded non-stop or nearly non-stop with difficult affect. I made a series on instagram about the dual process model of grief and how that can be a helpful framework for understanding the trans experience of 2025. The “DPM” is a model of adaptive bereavement coping (by Drs. Stroebe and Schut), which captures the importance of both loss-oriented bereavement processes and restoration-oriented bereavement processes. Loss-oriented processes primarily include experiencing and seeking understanding of feelings of loss and all the messy associated feelings. Restoration-oriented processes involve meaning-making and connection building in the aftermath of the loss — figuring out who you are in this new reality, but also avoidance and denial of grief. These bereavement experts argue that moving between grief and growth and between confrontation and avoidance is critical. Getting stuck in either dimension prevents adequate coping and healing.

Similarly, we need to be able to move in and out of confrontation of these difficult realities to some degree. There is no shame in letting yourself forget the suffering of others or your own suffering or fears for pieces of time so that you can be present to the joys and/or needs and/or connections in your immediate social field. The goal is balance, not getting stuck in confrontation nor in avoidance/disavowal.

Unless you are actively in need of directing all resources toward survival, coming inside from the hazy air and meditating or taking a bath or having a dance party with your kid or going on a date or eating something delicious and nourishing… these are valuable breaks. We can hold gratitude for the cognitive-emotional processes that allow us to employ disavowal in such circumstances. There’s something here about the capacity to hold the dialectic truths that the world is not fine, we are not fine and that in some moments we are at peace and energized and amused and feel good. (I wrote a little bit about this both/and back in January.)

The world is not fine. And we must reckon with that. And we will keep living meaningfully in an awfully not fine world.

“Currently” as of when I started this draft, though I’m happy to be finishing this post on my porch with air quality back to safer levels. (And the dynamic nature of this and many, though not all, of the threats and suffering I reference in this piece, is relevant to how we respond and survive as well I think…)

Do we have a collective sense of how we do this? Should I write about this piece of the process more?

That said, if you’re a trans person (or family of a trans person) and you have the means, I do think it’s worth considering getting to a state like Massachusetts where the state government has consistently (and with actions, not just words) supported trans people and trans healthcare. This isn’t the answer for even all of the people for whom it is accessible, but I name this to say there are safer parts of this country and maybe safer parts of the world for some of us and I don’t fault anyone for figuring out escape routes for themselves and/or others.

(largely thwarted and incomplete… talk about disavowal or perhaps denial)

Thank you so much for writing this! I work with clients who identify living with eco/political anxiety (as do I) and I have found a lot of relief in working from a Collapse Acceptance approach. The book Eye of the Storm by Terry LePage talks about this approach and I have found it really grounding. Avoidance works, until it doesn't. We can honour that avoidance and cognitive dissonance keep us safe for a period of time, but then it is important to address the issue we are protecting ourselves from. There is a lot in this post that resonates with the work I do around climate anxiety. Thank you.